A warm welcome to the church of Holy Trinity and St Mary, Berwick-upon-Tweed

In Depth History

Ours is the only Parish Church built during The Commonwealth of Oliver Cromwell (born 1599 – died 1658).

Designed by John Young of Blackfriars, foundation stone laid 1650 and opened in 1652, HOLY TRINITY replaced the medieval Church, which had stood a few yards to the south since 1190AD but was demolished shortly after the new church was opened.

With thanks to Canon Alan Hughes, vicar of Berwick 1994 – 2012 for this article.

Fashioned largely from the stones and timbers of Edward the First’s once great 13th century castle of Berwick-upon-Tweed (by then redundant following new defences by Elizabeth I), the site and fabric have witnessed almost 1000 years of history in both good times and bad.

With our mix of Gothic and Renaissance features, fine stained glass windows including 17thC Flemish Roundels sequestrated by Charles I from The Duke of Buckingham, unique Reredos by Sir Edwin Lutyens, original Communion Table used at our Consecration in 1662, magnificent Rose Window, Churchyard full of fascinating headstones including Viking and Plague Graves, there is much to interest.

Ours is the only Parish which used to be mentioned specifically in the Preface to The Book of Common Prayer, where the Monarch directed that “this book be used in all the Chapels of my Kingdom of England, Dominion of Wales and Town of Berwick-upon-Tweed” – such was the status of Berwick in our realm, the great ‘Bulwark defence’ against Scotland and her allies – changing hands between us 14 times, we now we get on famously, thanks be to God!

July 25th 2000 we celebrated the 350th anniversary of the laying of our foundation stone, the 340th anniversary of The Restoration of The Monarchy and 350th anniversary of the raising of THE COLDSTREAM GUARDS formed in 1650 as Monck’s Regiment of Foot by Colonel George Fenwick and his father-in-law Sir Arthur Hasselrigge. After battles at Dunbar and Edinburgh, the Regiment settled at Coldstream in the Scottish Borders before marching to London to lay down their arms for King Charles II upon His Restoration in 1660. Fenwick was Cromwell’s Governor of Berwick and caused the Church to be built, his memorial stone is set into our walls and reads “a good man is a publick good”.

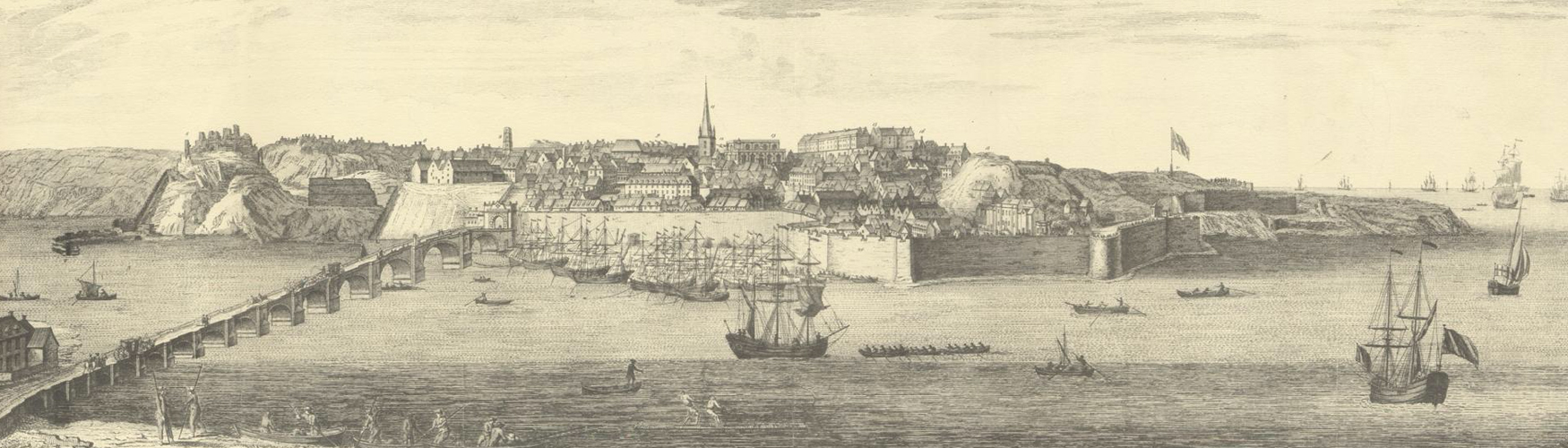

Fenwick was also a Founder of the Saybrook Community, Connecticut USA. Berwick-upon-Tweed is ‘twinned’ with Berwick in Pennsylvania and Berwick (now Casey) in Australia. Our Church is a jewel set within the crown full of architectural gems which is Berwick, described by Pevsner as ‘the most exciting Town in England” One and half miles of the finest Elizabethan defences in Europe surround our Town with original gateways and the first Barracks built for a Standing Army by Hawksmoor, an 18thC Guildhall and prison, early 17thC stone bridge, many fine Georgian Houses and fascinating alleyways. Standing at the mouth of the mighty River Tweed, where netsmen and anglers take the Salmon, we have excellent beaches, rolling hills and high mountains, moorland and forests and a wealth of Castles, Historic Houses and Holy Island cradle of Christianity within easy reach. We are a clearing house for seafood – with oysters, lobsters, langoustines, scallops, crabs, kippers and smoked salmon all readily available. I have never had a day bored in Berwick yet!

1996 marked the 700th anniversary of the sacking of Berwick and subsequent ‘hammering’ of Scotland by King Edward I. Edward ‘Longshanks’ knew the area between the Tweed and Humber as North-Humber-Land, focussing on figures like him can obscure other pilgrims through our fascinating landscape. Those who trouble to look around are greatly rewarded:

Edin’s Broch is just over the Border and into Scotland, built perhaps 5000 years ago.

Cup marks and carved circles atop the haunting rock at Roughting Linn south of Berwick, probably begun around the same time and now surrounded by enchanting woods which make a natural home for the spirits of our forebears who worked played and worshipped their Gods there.

Ancient burial mounds can also be found throughout the north of England. These long or circular ‘Barrows’ are rough constructions of earth and stone 2.5 metres high and anything from 8 to 16 metres in diameter, built to hold cremated remains of our ancestors sealed in earthen pots, dated by the fairly reliable carbon 14 test to somewhere around 1800 BC,

The Bronze-Age.

Bronze-age man gradually cleared the oak forests between the Tweed and the Humber in order to cultivate land raising sheep and barley – Berwick-upon-Tweed gaining its name Bar-Wick, as ‘the place of the Barley’.

Trading swords of bronze, knives of flint and jet ornaments for gold from Ireland and stone battle axes from Scandinavia, they wore woollen dress buttoned down the front and hunted deer, wild bulls, wolves, wildcats and pigs amongst the oak trees. After the Bronze-Age came Iron man somewhere around 800 BC and his age continues into our own as we develop his discovery of extracting the metallic content of ironstone. In 1836 the Danish archaeologist J.C.Thomsen defined three technological ages of man, Stone, Bronze and Iron, we often refer to the inhabitants of his third age as Ancient Britons.

Their new technology revolutionised the clearing of forest and cultivation of land by introducing iron scythes, axes, hoes and ploughs. Defence against invaders was strengthened by iron swords, spears, daggers and shields.

Alaric the Goth had attacked Rome and so Emperor Honorius headed home to help and left the Britons to fend for themselves. Picts and Scots scaled Hadrian’s Wall and laid waste the north of England.

In 446AD the Britons sent a message to the Roman Governor of Gaul (France) begging help, this letter came to be known as ‘The Groans of the Britons’. The Governor had his own troubles with Attila the Hun and was unwilling to weaken his own position. Vortigern the then leader of the Britons turned to the Saxons over in Germany for help which came in the shape of an army led by Hengist. So began another milestone in our history, the union of the Anglo-Saxons, which was to last with one or two rude interruptions by the Vikings, until the Norman conquest. With good reason these times came to be known as ‘The Dark Ages’.

Hengist liked what he saw over here and summoned his brother and together they seized the entire country for themselves, chasing the Scots and Picts back over the wall and the Britons into remote corners of the land. Legend has it that King Arthur fought a famous battle at Mount Baden in 515AD leading the Britons to Victory over the Saxons. It is thought that Mount Baden is what is now known as Eston Nab at Eston in Cleveland and there is certainly evidenceof a Saxon Camp there to this day. Any victory was short lived however, the Saxons eventually triumphed and set up government throughout Britain by dividing it into seven distinct Kingdoms known as The Saxon Heptarchy. The last and largest of these was North-humber-land.

This Kingdom was itself divided into two smaller units, Bernica between the Tweed and the Tees and Deira between the Tees and the Humber. Deira was Saxon for ‘wild beast’ perhaps reflecting the abundance of those animals which were hunted there.

No one knows for certain precisely when Christianity first established places of worship. It is probable that Christians came with Roman merchant ships. We do know that St Columba brought Celtic Christianity to the Isle of Iona off the Scottish mainland from Ireland in 563AD and St Augustine Roman Christianity to Kent in 597. The decision which should hold sway over Northumberland was made by Oswald after winning the Battle of Heavenfield in 634 declaring himself to be a Celtic Christian King. Oswald had an Abbey built at Whitby in 658 and ironically it was there that Abbess Hilda presided over an historic council in 664 which decided that Roman Christianity was to be the form recognised throughout England. The Celtic Saints were banished to the far north.

The Saxon Heptarchy was not a success, it was for ever at war within itself weakening its hoped for unity of kingdoms by tribal feuds and much bloodshed. When the Vikings laid siege to Lindisfarne in 793 they met with little resistance. Marching south they laid waste the countryside. A second wave in the form of The Viking Great Army of 866 further reduced what was left of Deira, the land between the Humber and the Tees. The Vikings then set about building their own settlements, leaving us to this day place names with their own ‘signature’ on the end, ‘by’ meaning farmstead. Saxon churches were burnt, along with monasteries which were the seat of all learning, lands and intellects remained uncultivated.

The Vikings eventually moved south, leaving the Saxon remnants free to rebuild their small communities. Fortunately for those living in southern Britain, King Alfred the Great defeated the Danes in a series of battles which drove them north once more much to the despair of the Saxons.

The last and most powerful Viking in the north was Siward who declared himself to be King of Northumbria. He terrorised the north but had one redeeming feature, like the Romans before him he kept the Scots and the Picts out of his territory. Siward died in bed in 1055 just eleven years before the Norman conquest and was succeeded by Earl Tostig who was then killed at Stamford Bridge near to York shortly before the Battle of Hastings.

King Harold made Morcar, brother of Edwin, Earl of Mercia, the third Earl of Northumbria.

After Harold’s defeat by William Duke of Normandy, Earls Morcar and Edwin had to give up their land but were allowed to retain their titles. William the Conqueror gave a man called Gospatric charge of both the land and armies of Northumbria. He was the son of Maldred, brother of Duncan, the father of King Malcolm of Scotland – Gospatric was soon to be grateful for his Scottish connections.

William was crowned King by Aldred Archbishop of York. His armies did not necessarily fight for the love of William, they were hired mercenaries and wanted payment. William levied severe taxes, especially in the north and this led to considerable unrest. There then followed a confident uprising against him in Northumberland when news spread that Swein the Dane was returning to our shores. He landed by the Humber but was defeated by William’s men. Now distrustful of the north, William sent one Robert de Comines and seven hundred men to secure Durham and take over as Earl of Northumberland. In January of 1069 Robert crossed the Tees into Durham killing any peasants he found there. When word spread to Durham a large army was rallied which utterly destroyed Robert’s band. Only Robert and his personal aide survived the slaughter, they took refuge in a house but were discovered, the house was burnt and as they tried to make their escape both men were beheaded.

Gaining in confidence the rebels mustered support all the way back to York. They trapped the Governor of York Castle outside the city walls and killed him. Word was smuggled out of York to William that the only Norman Garrison north of the Humber was now under siege. William realised that Edwin and Morcar had turned against him, and were plotting with Gospatric. He made a terrible oath to avenge his dead kinsmen in York and Durham. William was given to making oaths and often began them with the words “By God’s splendour ……” this time he added “I will harry the north!” Thus began an infamous chapter in our history known as ‘The Harrying (or Harrowing) of The North’ of 1069AD.

“For 60 miles between York and Durham every village was deserted and scarce a house left standing, the whole district being reduced by fire and sword to a horrible desert, smoking in blood and ashes. The land lay uncultivated for nine years, and a dreadful famine ensued, which reduced the wretched inhabitants to eat the flesh of dogs, cats, horses and even human carcasses, multitudes lay on the ground unburied, and the few that escaped the sword perished in the fields overcome with want and misery.” (The Reverend John Graves)

Gospatric fled to Scotland to seek refuge with his kinsmen. He survived for a time in Scotland producing a son and heir named after him. It was this Gospatric who witnessed the Charters granted to the Abbey of Scone in 1115 and Holyrood at Edinburgh in 1128. His son, Huchtred in his turn had a son who styled himself Helias de Dundas, having obtained a charter from Waldevus, son of Gospatric his uncle. This document, dated 1145 AD is thought to be held to this day by the Dundas family. The present Marquess of Zetland is the 27th in direct lineal descent from Gospatric, the Earl of Northumbria who stood against William the Conqueror.

The very last stand of the Britons against William was at Coatham Marshes on the Tees where arrow heads are still found to this day. It is said that, had there been a remnant of Britons able to ambush the by now vulnerable William at Bilsdale near Helmsley following the Coatham battle, history would have taken a different turn. Making his way home through the Dale William was caught in a spell of freak weather and separated from his army and left with only six men to guard him. Even today farmers in Bilsdale have a saying for someone on a cold day “swearing like Billy Norman” apparently passed down from father to son.

After Coatham, the desolation of Northumberland, from Bernica to Deira was complete. In 1070 King Malcolm of Scotland was able to wander south without challenge and destroyed any remaining villages, taking advantage to make the invasion he had feared to mount in 1058. It may have been this period which led to the naming of Northumberland as ‘any man’s land’.

The Association of Free Miners still dig in and around The Forest of Dean in Gloucestershire but not for long if ‘Europe’ has its way. Earning barely a living wage on one man plots the miners have been ordered to pay the same mine licence fee as full size commercial pits. They received their Charter from Edward the First March 30th 1296, 700 years ago this year. Edward was so impressed by the speed with which a group of his soldiers undermined the walls of Berwick Castle, that he granted them a charter to dig for coal wherever they wished. Any man apprenticed to a Free-miner for a year and a day and had attained the age of 21 could also then call himself a free-miner and so the tradition has passed down the ages. What brought Edward and his men to Berwick-upon-Tweed 700 years ago and why did he order them to undermine its walls?

“When asked where MAGNA CARTA was signed a student once replied, “on the bottom right hand corner?” – his answer trailing off into a question, or so it is claimed. I can in fact confirm that he was right. When set before John Lackland at Runnymede on June 15th 1215 by his Barons, King John did apply his seal to the bottom right hand corner. My wife’s uncle Geoffrey Sale found a copy of King John’s ‘Great Charter’ at King’s School Bruton when headmaster there, its eventual sale securing the financial future of his school.

The charter included promise to defend the “life, liberty and property” of the citizens of our land. John died of dysentery at Newark a year after Runnymede, fighting his Barons around the area of The Wash, supported by Dauphin Louis of France and French mercenaries! Before he died John had Pope Innocent III annul Magna Carta but it was to be reissued shortly after his son Henry III succeeded him.

Henry was in turn succeeded by his son Edward I. Edward no doubt chose to ignore the letter of the Great Charter’s law as he arrived on the outskirts of Berwick March 30th 1296. He rode on his favourite horse Bayard at the head of an army estimated by contemporary observers to comprise 30,000 foot soldiers, 5,000 mounted men at arms and over 100 ships. Whether or not promised civil rights, seven hundred years ago this March, Berwick, hitherto the foremost of the 4 original Royal Boroughs of Scotland, was to suffer such a reversal of its former fortunes that it was never to recover. One historian puts it plainly “the town was ruined for ever, and the greatest merchant-city of Northern Britain sank from that time into a petty seaport”

In our own time wars are conducted in front of television cameras, we can actually view human conflict live from our armchairs. Northumbrian families watched their sons and daughters fight in the Gulf War and even now can catch up on our soldiers progress with IFOR in former Yugoslavia, anxiously trying to guess through the comments of journalists what might happen next. Reputations of Warlords are paraded for all to see almost as they are made. One wonders just how much or how little the citizens of Berwick knew of Edward’s reputation, as they prepared to defy him and taunt him with a name.

‘Longshanks’ was a title by which he would be known for the rest of his days, days that many Berwickers would not live to see.

After witnessing the young Prince Edward attack upon an individual, one subject remarked “I look forward with dread to the day when he will become King” He embarked upon a Crusade to The Holy Land in 1270 where amongst other exploits he attacked Nazareth, the home village of Jesus, killing everyone he found there. Although his father died in 1272 things had become so stable here at home Edward did not return to be crowned until 1274.

Determined to be seen to be King not simply in name but also in reality, immediately after his Coronation he focussed on what he perceived to be the four main threats to his Kingship, the Welsh, the Jews, the Scots and the French.

He waged two systematic campaigns against the Welsh, the first 1276-77 led to the overthrow of the great Llewellyn ap Gruffyd. Turning then to his second perceived threat he had all Jews in Britain arrested, hung 267 of them and banished the remainder.

Returning to the ‘Welsh problem’ in 1282 his attacks led to the death of the Great Llewellyn and the capture of his brother David whom Edward had hung, drawn and quartered at London.

Berwick Railway station now covers the ground where once stood the Great Hall of Edward’s castle. There seems a certain arrogance about the Victorians, apparently concluding that no age had been as great and technologically advanced as theirs and that the world not see the like again. Berwick Castle site will ever remain a damning memorial to that view.

Granted that by that time most of the castle had been removed and used to build Berwick Parish Church and many other fine structures, but surely they could have refrained from ruining the site further and run the railway by some other route. Passengers descending the steps to the platforms today read an impressive plaque recording that this was where Edward held his ‘consultations’ with most of his Court over the period 1291-92 to determine who should rule Scotland.

After the death of Alexander III of Scotland the line passed to his little grandaughter Margaret. The ‘Maid of Norway’ as she was known was only three when she became Queen and all hopes that she would marry Edward’s son and ‘solve the Scottish problem’ were dashed when she died on a sea journey aged barely eight. Thirteen contenders for the Crown of Scotland now surfaced, which certainly proved unlucky for Berwick. On advice and after skilful manipulation Edward managed to have this list whittled down to three, John Balliol, Robert Bruce and John Hastings. He obtained agreement from all three that decision should be taken by a court assembled at Berwick under his Kingship and furthermore they all agreed that Edward should be King of Scots until judgement was made.

For Edward, the only serious candidate was Balliol, he had been assured privately by a Scottish Bishop that Balliol would prove both a good King for Scotland yet also one loyal and subservient to the English Crown. The predictable decision came and Balliol declared King. Edward departed for Westminster happy that Scotland was in a safe pair of hands. It is said that over the coming months Edward took every opportunity to send for Balliol to show who was really in charge of his ‘united’ Kingdom.

1294 Edward felt confident to respond robustly to Philip of France’s impertinent attack on and subsequent capture of Gascony. Without any thought in his mind that he would be refused, Edward ordered Balliol to send an army to France in support of his

cause. The willing but hapless Balliol was outvoted by the Scottish nobles who marked their independence and defiance by deporting all Englishmen of noble birth and seeking a treaty with France.

Edward responded swiftly and Berwick entered the cross-fire. Balliol was ordered to declare loyalty to Edward and refused. He was then ordered to surrender Berwick Castle to enable Edward to use it as a base for an inevitable war between England and Scotland, again he refused. Did the Scots know of Edward’s destruction of Nazareth, they must surely have heard of the hanging of the Jews, the utter destruction of Wales?

Ignorant of Edward’s reputation or foolhardy, perhaps just fiercely confident? they began to make small independent incursions over the border country from coast to coast without Balliol enraging Edward – the Die was cast. Clearly Edward had no intention of destroying Berwick, he needed the Town as a base, his anger was directed further north. Sheer frustration must have fired him that Good Friday, for so it was with a terrible irony that Good Friday fell on March 30th in that fateful year of 1296.

The day kept by Christians as the day of dereliction endured by Jesus at his Crucifixion was to mark a crucifixion of the inhabitants of Berwick. The Romans carried out ‘decimation’, they punished by killing every tenth man. Edward ‘Longshanks’ as Berwickers named him did not decimate Berwick, he virtually wiped out the population. It has been claimed that 8,000 men women and children were killed, others put the figure as high as 15,000. The scale of the losses have long been a subject of debate and some consider such numbers to be wildly overstated. I cannot help but look upon the present population of Berwick today, not much greater than 700 years ago in 1296 and ponder images handed down from those who recorded the events “the citizens fell like leaves” “for a day and a half those of both sexes perished, some by slaughter, some by fire” “there was blood enough to run the mills” “people fled into the Churches for protection but were slaughtered there” with a feeling that nothing could overstate what must have taken place over that 1296 Good Friday to Easter Day.

The destruction and capture of Berwick can be read in many places, suffice to say that that 30th March must have been the blackest day in our history. After fortifying Berwick Edward headed north and by the end of the year forced Balliol into surrendering the Crown at Brechin. He appointed his own regents for Scotland and removed the famous Coronation ‘Stone of Destiny’ from Scone Palace to Westminster where it was set into his own Coronation Chair. This was his way, after defeating the Welsh he triumphantly returned home carrying the Crown of Arthur and a fragment of the true cross. History does not record what he brought home from Nazareth. March 30th marks the eve of Palm Sunday this 1996 and I am not sure how to mark this 700th anniversary, hardly a cause for celebration. I shall certainly feel the poignancy of the anniversary, as I lead my congregation in remembering the entry of Edward into Berwick, slaying all before him and Jesus into Jerusalem, riding on a donkey welcomed as a true King. I shall certainly pray for a healing of the pains of the past and a hallowing of those of us who inhabit God’s present.

Berwick today is a vibrant Border Town with new industries to stand alongside the Salmon Fishing still practised by a few netsmen. Pevsner once described Berwick as “the most exciting town in England”. Tourists come from all over the world to visit this unique town comprising many unique and historic buildings. Remains of Edward’s Castle, the Elizabethan Walls considered the best preserved in Europe and upon which Elizabeth I spent twice as much than she spent on the whole of defence for the whole of her reign for the whole of her realm! Holy Trinity Parish Church is the only one to be built in a distinctive style at the time of Cromwell’s passing through Berwick en route to seign Dunbar and Edinburgh. The original preface to The Book of Common Prayer states:

“this book shall be used by all that officiate in all cathedral and collegiate churches and chapels and in all chapels of colleges and halls in both the universities and the colleges of Eaton and Winchester and in all parish churches and chapels within the kingdom of England, Dominion of Wales and town of Berwick-upon-Tweed.” – adding to our uniqueness.

A journey broken for a few hours in Berwick whether heading north or south would be well rewarded. Perhaps a resolution made to return for a holiday or short break to explore a delightful Town nestling on the north banks of The River Tweed. The view from the Border Railway Bridge is magnificent but only gives a glimpse of what lies within our walls. Museums, art galleries, The Main Guard Room restored by The Civic Society, The Taste of Berwick exhibition in our Barracks (the first to be built for a standing army), the remarkable Guildhall, the Elizabethan walls and bastions, the bridges and quayside and Parish Church. Not to mention the shops and restaurants – contact our Tourist Board for information packs.

Canon Alan Hughes

former Vicar of Berwick

Roughting Linn